The last time I was at my parents’ house, my dad jokingly

made a reference to “cow lips” in hot dogs.

I had to cringe. With labeling requirements that reveal all ingredients in food products, why does the myth of hot dogs being made of "unspeakable" animal parts still exist? Its longevity

may be due to a hot dog’s inner appearance.

The springy, smooth, reddish brown hot dog is a far cry from marbled,

fibrous beef chuck. However,

that beef chuck can be turned into a hot dog with the right machinery,

ingredients, and cooking process and still deliver the protein, iron, and other nutrients promised by a fresh cut of beef. In a

previous post, I explained the non-meat ingredients of a hot dog. Today, let’s talk about the meat.

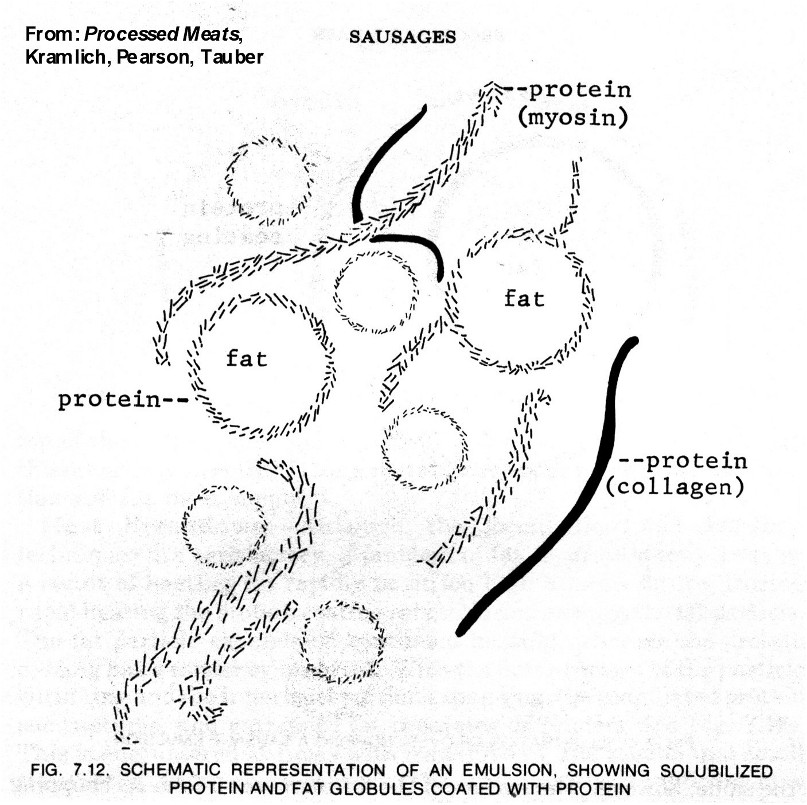

A hot dog is an “emulsified” meat product. An emulsion is a stabilized mixture

of solid particles dispersed throughout a liquid component (Aberle, Forrest,

Gerrard & Mills, 2001). In an

emulsified meat product, the particles are fat and the liquid component is

water containing salts and proteins (Aberle et al., 2001). While water and fat would naturally not mix

together, proteins with both hydrophobic (“water-fearing”) and hydrophilic (“water-loving”)

parts can hold the fat and water together (Figure 1).

Myofibrillar proteins (the stringy, fibrous muscle proteins that allow

for movement) hold fat and water together well, but for the myofibrillar

proteins to be of use, they must first be extracted from their original positions

in skeletal muscle. A bowl chopper (think of a king-size food processor) will first dice ground lean meat into tiny pieces, thereby increasing the surface area of the meat. Salt will extract the tightly bound myosin

and actin from each other, and these liberated proteins will then interact with the

fat and water which are later added to the mix (Aberle et al., 2001).

Figure 1: Proteins coat fat particles to allow the fat to be held within the water phase of an emulsified product.

If you are unfamiliar with proteins and how they are put

together, this might be a little confusing.

The main point, though, is that parts of the animal with LOTS of

myofibrillar protein (i.e., skeletal muscle) can interact with water and fat

much better than parts of the animal with little myofibrillar protein. Another type of animal protein is called “stromal

protein,” perhaps better known as “connective tissue.” The main stromal proteins are collagen and

elastin. Collagen is found in skin,

lips, ligaments, bones, and blood vessels, and is, in fact, the most abundant

protein in an animal’s body (Lodish, Berk, Zipursky, et al., 2000). However, it is an “insoluble” protein,

meaning it is not broken down as myofibrillar proteins are broken down by

salt.

Now, you might be wondering, “What does this have to do with

hot dogs?” Remember that hot dogs are

emulsified products, and the emulsion can only be stable if the components bind

together well under stress. Meats that

have high binding capabilities are those high in myofibrillar proteins such as

bull and cow meat, skinless poultry meat, lean pork trimmings, and beef chucks

(Aberle et al., 2001). Meats with a high

percentage of stromal protein include the infamous “filler meats:” lips,

stomachs, snouts, skin, and tripe (Aberle et al., 2001). If hot dogs contain a large percentage of

collagen-rich meat, the collagen will melt during heat processing and then

congeal as gelatin when the hot dogs are cooled (Aberle et al., 2001). These hot dogs will undoubtedly not be what

the producer or consumer wanted. Since skeletal muscle already contains some collagen due to the presence of blood vessels and connective tissue (Figure 1), deliberately increasing the amount of stromal protein by adding lips or snouts is not greatly practiced.

Hopefully you now understand why the joke of “cow lips” in

hot dogs is not so funny. Producers want

their customers to be happy with tasty, nutritious, good looking products, and

this can only happen with the right ingredients. If you are still curious about what’s in your

hot dogs, check the ingredients label.

All filler or “variety meats” must be declared on the label, including

the specific meat’s name (e.g. “heart”) (National Hot Dog & Sausage

Council, 2013). So the next time you’re

at a weenie roast and someone doesn’t want to eat something made of the “less

savory parts of an animal,” show them the ingredient list and enlighten

them! You can even whip out words like "emulsified" or "myofibrillar" to really impress them.

References

Aberle, E.D., Forrest, J.C., Gerrard, D.E. & Mills,

E.W. (2001). Principles

of Meat Science (4th ed.).

Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Lodish, H., Berk, A., Zipursky, S.L., et al. (2000). Molecular

Cell Biology (4th ed.). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

National Hot Dog & Sausage Council (2013). How hot

dogs are made: The real story.

Retrieved from http://www.hot-dog.org/ht/d/sp/i/38597/pid/38597.

emulsion diagram: http://lpoli.50webs.com/Tips.htm

.